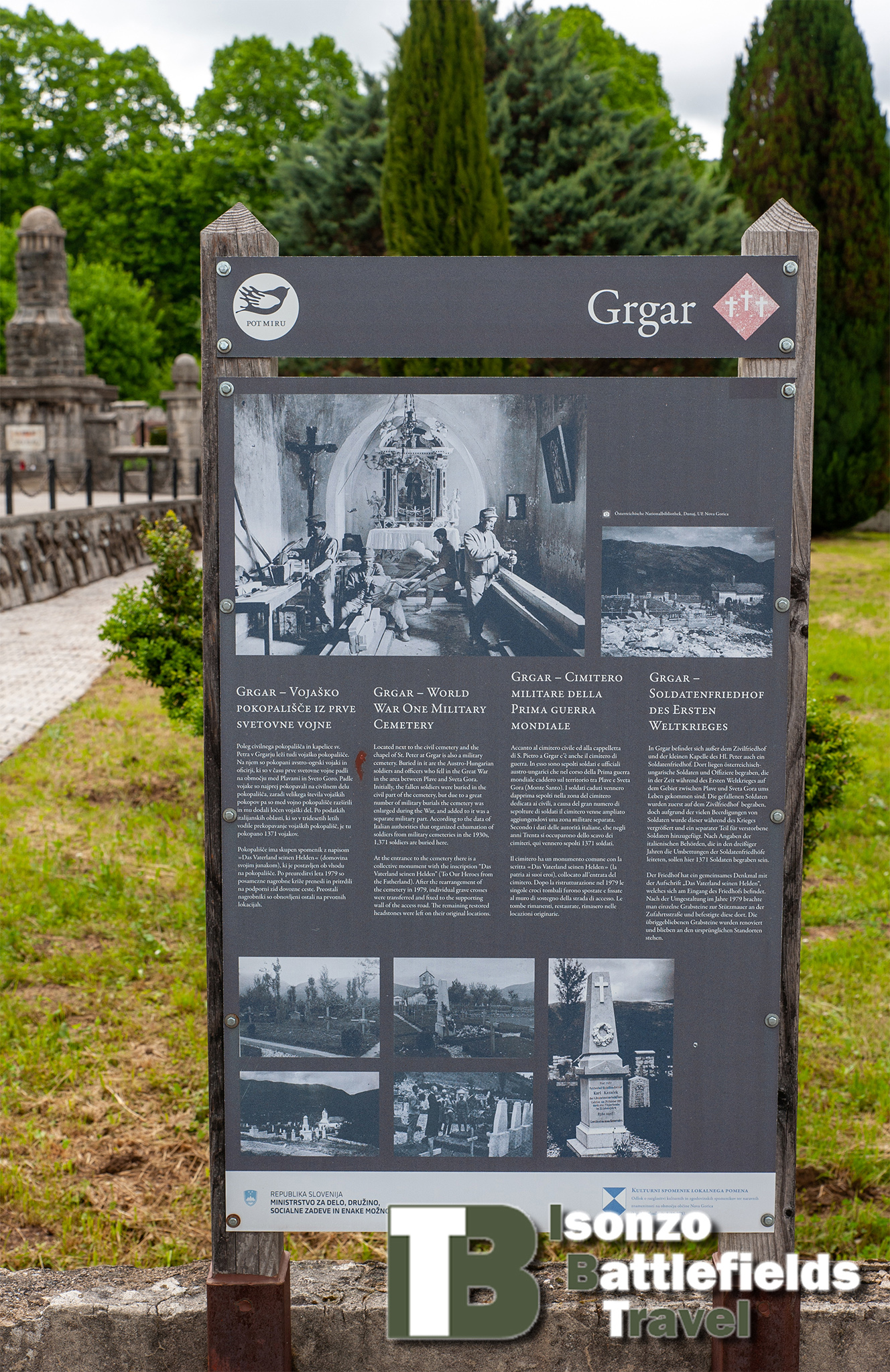

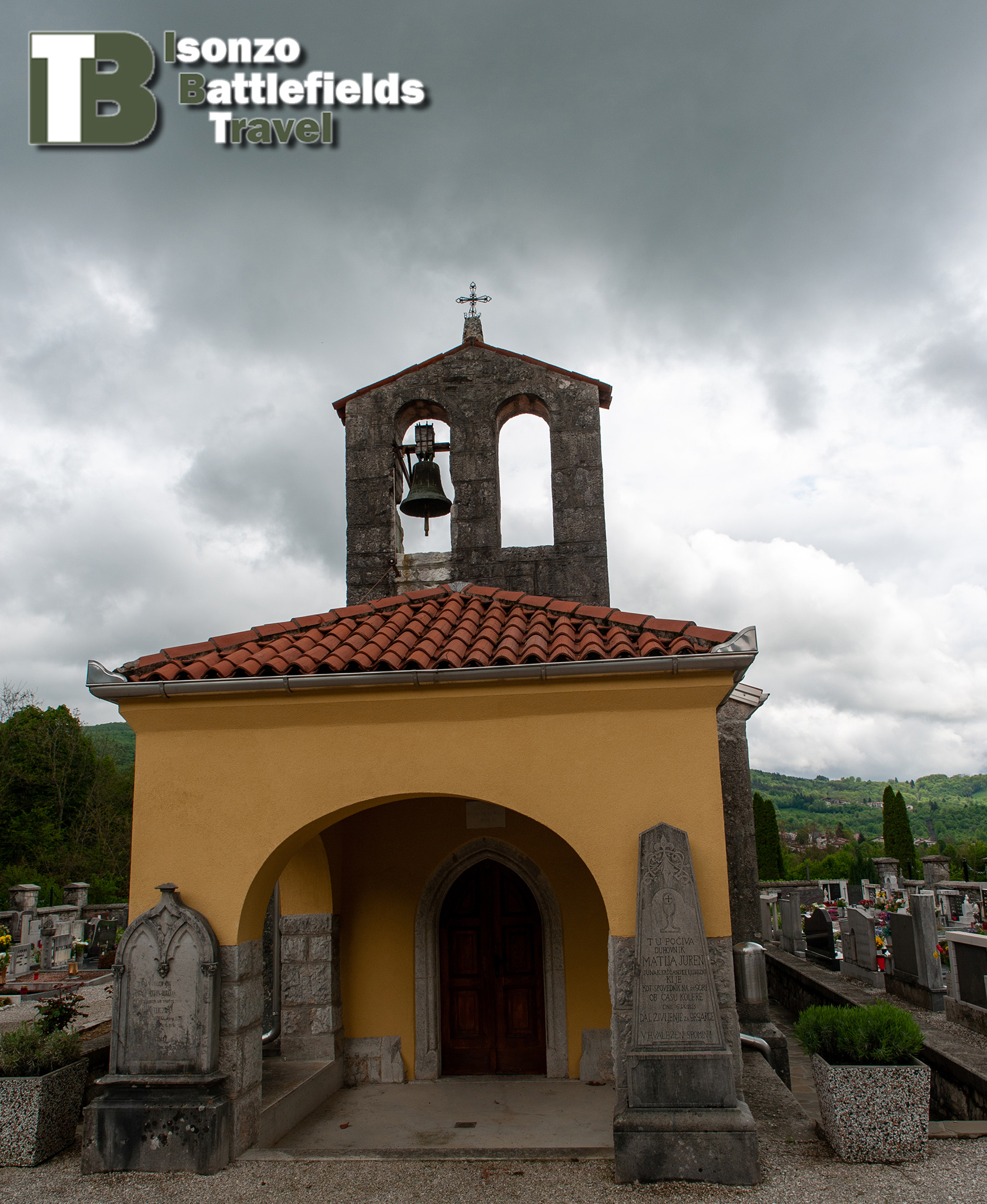

Austro-Hungarian military cemetery WW1, Grgar

Grgar is a town on the edge of the Bainsizza (Banjšice in Slovene) plateau.

The Bainsizza (Banjšice in Slovene) is a misnamed plateau to the north of the strategic city of Gorizia on the Italian Front of 1917. The city had been captured during the the Sixth Battle of the Isonzo in 1916 in hopes that it would provide a launch pad for the Italian Army to the highly prized port city of Trieste. However, Austro-Hungarian forces retained control of several key mountains north of the city most of the rugged Carso Plateau to the south. During the previous ten battles along the Isonzo, the Bainsizza was considered impassable by both sides, and it remained lightly defended during the summer of 1917.

The Italian Army had previously resisted attacking the area, which presented incredibly challenging terrain. It is a hybrid of pretty pastoral farmland and towering limestone mountains separated by narrow ravines. However, by this stage of the war there was a secondary issue north of the Bainsizza. Near the town of Tolmino, the enemy held a bridgehead across the Isonzo. It was great strategic threat to both Italian armies in the area and had to be dealt with. Commando Supremo concluded that both challenges could be overcome by a major attack through the Bainsizza—the Tolmino bridgehead and the mountains around Gorizia could both be flanked by a successful breakthrough. From past experience, the planners knew that the plateau would be lightly defended, at least for the opening assault.

This was the genesis of the Eleventh Battle of the Isonzo. The main objective was to capture the Bainsizza Plateau. Unfortunately, the planners combined this somewhat creative solution with the old standby scheme for capturing Trieste by just pounding very, very hard through the Carso. Guided by this two-pronged strategy, Italy’s Second and Third Armies began the largest of all the Isonzo Offensives on 19 August 1917.

The new target for 1917, the Bainsizza, rises so rapidly and so high from the Isonzo that a frontal assault would be nearly suicidal. For once, however, tactics were adjusted to the situation. In an admirable bit of creativity it was decided that the plateau, with the help of 14 bridges to be placed across the river by engineers, would be assaulted from the north at a section where the terrain was not as challenging for assault troops. Despite heavy casualties, the men of the 24th Corps crossed the river, advanced behind an effective artillery barrage, forced their adversaries to withdraw, and eventually occupied about half of the plateau. On the south edge of the plateau a secondary attack was staged from Mte Kuk, resulting in the capture of Mte Santo, which had resisted the Italians in the Tenth Battle. These advances around the plateau stopped, however, when the artillery support was not able to follow farther and the Austro-Hungarian forces—always good on the defense—started taking advantage of the many caverns and hiding places provided by the Bainsizza’s weird geology.

The Italian Army, which entered the fighting with a huge manpower advantage, still suffered 150,000 killed and wounded, the Austro-Hungarian 5th Army about two-thirds of that figure by the 12 September conclusion of the battle. Nevertheless, after the success of the Sixth Battle of the Isonzo when Gorizia was captured, the Eleventh Battle was the most impressive military achievement by the Italian Army on the Isonzo. Their opponents were nearing the breaking point and were about out of troops to reinforce the sector. However, their concerned German allies were watching and the decision was near for them to help their partner. Italian Supreme Commander Luigi Cadorna sensed the Germans were about intervene and decided to get ready. His preparations, though, would prove inadequate in preventing the cataclysm to come, at Caporetto.

Source: Roads to the Great War